Curate

- Museum: Museum of the History of Science

- Description:

Sketchbook page for Curate workshops at the Museum of the History of Science

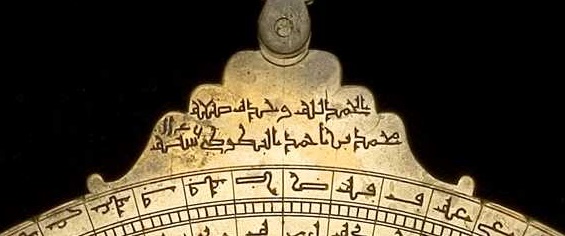

Astrolabe 37148

Inventory number: 37148

Origin: Syro-Egyptian

Date: 1227/8 A.D

Materials: Brass with gold and silver damascene work

Maker: Abd al-Karim, Jazira (Mesopotamia)

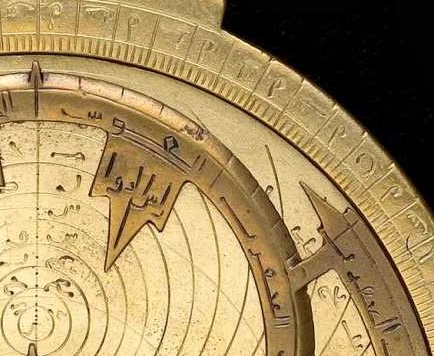

Signs of the Zodiac

One of the outer engraved rings on this astrolabe illustrates the signs of the zodiac. The houses of the zodiac show star constellations through which the Sun appears to move over the course of a year.

Unusually, the figures on this astrolabe are mirror images, one giving an earth-centred view (looking up into the sky) and the other a view from outside the celestial sphere.

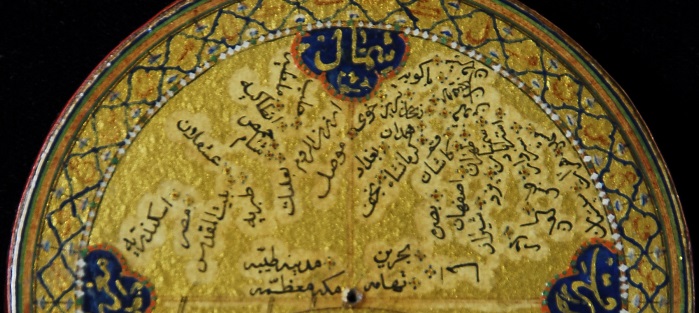

Lunar Mansions

A remarkable feature of this astrolabe is the pictorial set of lunar mansions found on the back. While many astrolabes include a list of lunar mansions, the pictorial representations found here make it unique. Similar to the sun’s relationship to the Zodiac, the Lunar Mansions show the position of the moon relative to fixed stars, as it orbits around the Earth. In this close up we see the mansion of the winged horse (المقدم — al-Muqqadam).

The lunar mansions link the astrolabe to a rich tradition of astral magic. Numerous Arabic texts associate the lunar mansions with talismans, which were used in all manner of magic, both beneficial and harmful such as medicine and love magic.

Sultan Abū-l-Fātih Mūsā

This astrolabe was made for the sultan Abū-l-Fātih Mūsā, Saladin’s nephew, who ruled over parts of Mesopotamia (Iraq), Syria, and Armenia in the 1210s and 1220s. An inscription includes about thirty honorific titles and terms of praise for him minutely inlaid in gold around the entire front rim.

The book of fixed stars

An inscription on the surface of the celestial globe states that the star constellations on the globe have been drawn according information written in the ‘Book of the Fixed Stars’ by Abü-l-Husain ‘Abd al-Rahman al-Süfi.

Al-Süfi (903-986 A.D.) was one of the greatest Muslim astronomers, and his illustrated ‘Book of the Fixed Stars’, is ‘one of the three masterpieces of Muslim observational astronomy’ (Sarton).

Silver Stars

The elaborate silver inlay (Damascene) used to represent the stars suggest that this globe was probably made for a wealthy patron. The body of the globe is made from brass.

Celestial Globe

Inventory number: 44790

Date: 1362/3 A.D

Origin: Iran/Persian

Materials: Brass with inlaid silver stars

Celestial globes

The Islamic tradition of the celestial globe was originally based on the work of the Greek astronomer, Claudius Ptolemy, of 2nd-century Alexandria. The practice of astronomy flourished in the early centuries of Islam with a number of significant observatories and Muslim astronomers contributing to the growth of astronomical knowledge.

A peculiar feature of Islamic globes is the way in which the constellations are depicted as if seen from Earth even though the celestial sphere as a whole represents a viewpoint from outside the sphere.

The axis of the globe can be adjusted for various latitudes in the northern hemisphere.

Velvet case

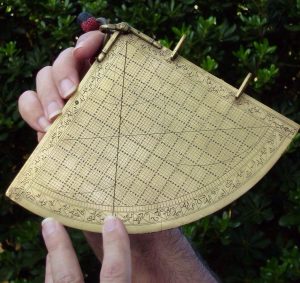

The quadrant still has its original case of velvet which is decorated with metal wired peonies and lined with silk. Known as brocade, these decorated fabrics were used for cushions or clothes in princely houses. They were also exported to Europe as luxury goods.

Lacquered wood quadrant

This quadrant is made of a lacquered wood that was prized in Persia and Turkey and often used for making pen-boxes and book covers. Islamic ‘lacquers’ were actually varnishes rather than the latex resin that was originally used by Chinese craftsmen.

Under the varnish, delicate floral arabesques have been painted in gold, in a typical Ottoman style.

Quadrant

Inventory number: 15598

Date: 1682/3

Origin: Turkey

Materials: Lacquered wood and velvet brocade

Three in one!

The quadrant was a common and important mathematical instrument. This instrument combines 3 different types of quadrant into one.

On one side is an ‘astrolabe quadrant’. This instrument “folds” the markings and functions of a circular astrolabe into a quarter circle. Overlaying this is an “horary” quadrant which has hour lines used for time telling.

On the other side is a sinecal quadrant that can be used to make trigonometric calculations.

The quadrant would have been read by using a plumb line and bob (now missing), attached in the top corner and that swung freely over the curved edge.

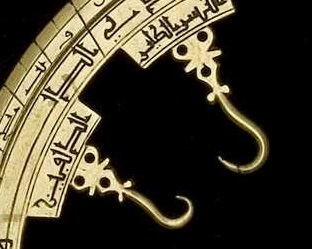

Zoomorphs

On the rete, which weaves in and out to create a map of the stars, two of the start pointers are depicted by a bird. The use of an animal, normally a bird, to depict one of the stars is known as a zoomorph.

Lahore Astrolabe

Inventory number: 47376

Origin: Lahore, Pakistan

Date: c.1570 A.D

Materials: Brass and Silver

Mughal Design

The design of this kursi (the ‘throne’) is typical of astrolabes from the Mughal empires in India – a high triangle elaborately pierced in a floral design.

The rete also follows a floral design. There is a great variety of styles in design of the rete, as well as remarkably persistent traditions. Unlike a Persian style astrolabe it remains simple, with little engraving.

A Family of Makers

This astrolabe is made by Allah-dad, who has signed the back of the instrument with the inscription “the master craftsman Allahdad, astrolabist of Lahore”.

Allah-dad founded a workshop in Lahore and the tradition of instrument making continued in his family for many generations. The museum has four other instruments made by Allah-dad’s descendants.

Click here to see an astrolabe made by Allah-dad’s grandson

Click here to see a celestial globe made by Allah-dad’s great gransdon

Sinecal Quadrant

Inventory number: 28781

Origin: Iran, Persia

Date: Late 18th century

Materials: Wood

Wooden quadrant

This simple sine quadrant, made from wood, would have included sights and a weighted cord (now missing) that would have been used for astronomy, surveying and mathematical calculation. Quadrants were made from a wide variety of materials and varied in value and finesse. The curved edge is marked with an angle scale from 0-90 degrees.

A Sine Quadrant

Sinecal Quadrants can be used to make quick trigonometric calculations. Today we make these calculations using the sine, cosine and tangent functions on our scientific calculators.

The straight edges are divided into 60 units which is called a sexagesimal scale. This base 60 scale comes from ancient Babylonian numbering systems. We still use a base-60 system in our division of time today.

Astrolabe 47632

Inventory Number: 47632

Origin: Syro-Egyptian

Date: 9th century

Materials: Brass

Maker: Khafif

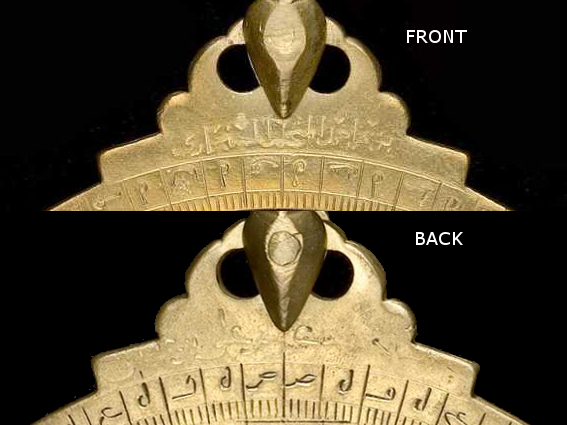

Dagger Star Pointers

There is a great variety of styles in rete design, as well as regional traditions. Stars can be represented figuratively, as birds and fish, or the whole surface can be covered in decorative engraving. The ‘dagger’ style of the star pointers on the rete is characteristic of the earliest instruments made in the 9th-century.

For other rete designs, click here

Makers and Owners

The Kursi (or ‘throne’) of this astrolabe has two inscriptions.

On the back is engraved: “Made by Khafif the apprentice of Ali ibn ?Isa”.

The astrolabe maker referred to is probably Alî b. Isà al-asturlâbî, a famous astronomer and instrument maker who flourished in Baghdad and Damascus c.830-832 A.D., and wrote one of the earliest treatises on the astrolabe.

On the front is engraved: “For Ahmad the astronomer of Sinijar”.

Astrolabes have important astronomical functions and were used as an instrument for measurement and instruction. A very wide variety of things can be calculated including the time, the date, prayer times and the altitude (height) of the sun, as well as use in surveying.

Religious uses

An inscription on this astrolabe tells us that it was ‘given as a bequest’ to the minaret of Idrīs at Fez, Morocco. This means that it belonged to a Mosque.

In the medieval Islamic world, science and religion were closely linked. Astronomical observations and calculations were important for religious practices. On this astrolabe we see special lines inscribed on the mater (front side) that were used for the calculation of Muslim prayer times.

Astrolabes could also be used to locate the direction of the Qibla, that is, the direction that Muslims should face to say prayers.

Trefoil star pointers

‘Al-Ankabut’ literally means ‘spider’, but it is also the Arabic name for what is known in Latin (and now English) as a rete: the rotating part of an astrolabe which displays the sun and stars.

The al-ankabut is cut and filed from a single sheet of metal. The essential elements of the structure are the off-centre zodiac circle showing the pathway of the sun, and the pointers representing bright stars in the sky.

There is a great variety of styles in al-ankabut design, as well as remarkably persistent traditions. The pointers on this rete have trefoil style bases that are seen in many North African astrolabes.

Ahmad al-Baṭṭuṭī

The inscription on the back of the throne bears the name of the astrolabe maker: ‘Praise to God alone. Made by Muhammad b. Ahmad al-Baṭṭuṭī, year 1146 [A.H.]’

Ahmad al-Baṭṭuṭī was one of the most productive astrolabe makers in North Africa. The museum owns two astrolabes that were made by al-Baṭṭuṭī, but unfortunately we don’t know a huge amount about his life. Although scientific instruments were made all over Africa, the tradition of instrument making was strongest in Morocco where instruments were manufactured for over 500 years.

Astrolabe 51459

Inventory number: 51459

Date: 1733-4 A.D

Origin: North Africa

Materials: Brass

Astrolabe 46681

Inventory number: 46681

Date: 1719/20 A.D

Origin: Isfahan, Persia

Materials: Brass

Abd-al-A'imma

This astrolabe is both ‘made and decorated’ by ‘Abd al-A’imma, and dated 1132 A.H.

‘Abd al-A’imma, who was working in Persia in the first two decades of the 18th-century, is one of the most famous names in the history of astrolabe making. Although very little is know about his life, more astrolabes are known bearing his name than that of any other maker, east or west.

‘Abd al-A’imma’s astrolabes were so sought after that many forgeries have been made.

Made for a Persian Prince

This astrolabe was made for ‘Alīqulī, a prince of the royal Safavid family who ruled in Iran from the 16th– to the 18th-century.

Many astrolabes were made for princes or other wealthy dignitaries; they were objects of great value, fit for royalty, magnificent in design, and an expression of power through connection with the divine cosmos.

Qibla Indicator

Inventory number: 43645

Date: 19th century

Origin: Iran, Persia

Materials: Unlacquered wood

Qibla-numâ

One of the five pillars of Islam is for Muslims to pray five times a day in the direction of the hold city of Mecca. The Qibla is the compass direction towards Mecca at any particular place.

In the top half of this instrument is a map showing the locations of different cities in relation to Mecca. Each town is named in Arabic and marked by a tiny blue and red arabesque.

By orientating themselves to the north using the compass, the user would be able to use the map to find the direction of Mecca.

See an example of a complete Qibla-numâ instrument here.

Compass

Through the window you can see a very small compass.

By orientating themselves to the north, the user would be able to use the map in the top half of the instrument to find the direction of Mecca.

The first known description of a compass used to locate the Qibla (direction of Muslim prayer) was in the 13th century.

Babylonian sundial

The bottom half of this instrument includes a sundial. The angled lines mark Babylonian hours. Babylonian hours divide the day into 24 equal hours, beginning at sunrise.

There would have been a pin gnomon (short stick), now missing, which would cast a shadow to indicate the time. It would have fitted in the small hole just above the compass needle.

Astrolabe template

Inventory number: 52332

Date: 18th century?

Origin: Persian

Materials: Wood

Brass blank

The production of astrolabes requires great skill in metal work but also a high level of mathematical understanding, particularly of spherical geometry. The techniques used include casting, drilling, filing, and engraving.

In the middle of this template there is a brass ‘blank’. With the help of a straight rule, the astrolabe maker would use the degree markings around the circular scale to engrave the instrument. The template allowed copies to be made easily and quickly.

The outer scale is a circle of 360° divided to each degree and numbered clockwise in abjad numerals, 0-5-10-5-20 … 360; Abjad numerals use letters of the Arabic alphabet to represent numbers.

There are other scales to allow for other mathematical functions such as the shadow-square which was used to measure the height of an object using its shadow.

Scales

The outer scale is a circle of 360° divided to each degree and numbered clockwise in abjad 0-5-10-5-20 … 360; within the degree divisions in the upper semi-circle a second series of abjad numerals runs 5-10-15-20-25 … 90-90-85-80 … 5. Abjad numerals use letters of the alphabet to represent numbers.

Within the lower semi-circle are two cotangent scales corresponding to the divisions of the shadow-square across the lower two quadrants. Shadow squares are used to measure the height of an object using its shadow.

Qibla Compass

Inventory number: 34566

Date: 18th century

Origin: Iran, Persia

Materials: Brass, with cloth carrying pouch

Pin-gnomon Dial

The hole in the centre of the top metal place would have held a pin-gnomon. The shadow cast by this stick would have been used to measure time from the movement of the sun.

The angled lines engraved on the plate mark Babylonian hours. Babylonian hours use a sexagismal system, meaning that time is divided into units of 60. We use the same base-60 system today…60 second to a minute…60 minutes to an hour.

Azimuth of the Qibla

Around the side is an ornamental inscription, giving instructions for finding the azimuth of the Qibla.

The Azimuth is the location of an object expressed as the angular distance from the north or south point of the horizon, to the object in question, in this case the holy Kaaba in Mecca.

Compass

Below the cut out window is a compass. The four cardinal points (North, South, East and West) are engraved on the top plate.

Qibla Compass

Inventory number: 33746

Date: c. 1800

Origin: Arabic

One of the five pillars of Islam is for Muslims to pray five times a day in the direction of the hold city of Mecca. The Qibla is the compass direction towards Mecca at any particular place. This pocket qibla indicator allows the qibla to be found using a compass and moveable pointer with the help of a geographical table engraved on the inside of the lid which gives the qibla for various towns and cities.

Link: http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/ancient/cultures/astronomical_instruments_03.shtml

The Qibla is the compass direction towards Mecca at any particular place. To help in finding the correct direction of prayer, many Islamic instruments carry geographical tables giving the Qibla for various towns.